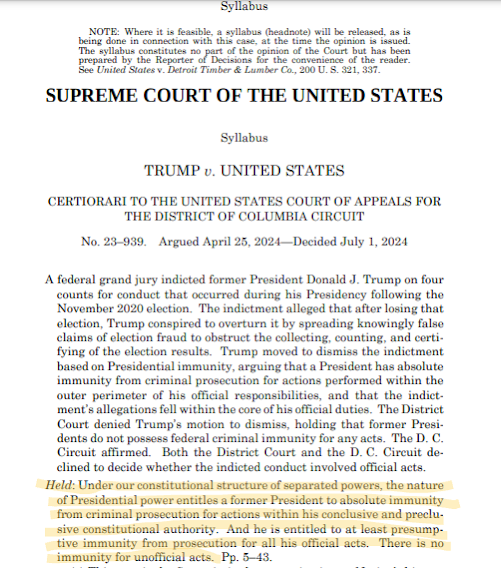

Gotta admit I never really paid attention to the significance of the two words "herein granted" in Article 1 (Legislative Branch) but conspicuously absent in Articles 2 and 3 (Executive and Jusdicial Branches, respectively).

|

| Source: Constitution Center |

"""Hamilton and Madison.—Hamilton’s defense of President Washington’s issuance of a neutrality proclamation upon the outbreak ofwar between France and Great Britain contains not only the lines but most of the content of the argument that Article II vests significant powers in the President as possessor of executive powers not enumerated in subsequent sections of Article II. Hamilton wrote: “The second article of the Constitution of the United States, section first, establishes this general proposition, that ‘the Executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.’ The same article, in a succeeding section, proceeds to delineate particular cases of executive power. It declares, among other things, that the president shall be commander in chief of the army and navy of the United States, and of the militia of the several states, when called into the actual service of the United States; that he shall have power, by and with the advice and consent of the senate, to make treaties; that it shall be his duty to receive ambassadors and other public ministers, and to take care that the laws be faithfully executed. It would not consist with the rules of sound construction, to consider this enumeration of particular authorities as derogating from the more comprehensive grant in the general clause, further than as it may be coupled with express restrictions or limitations; as in regard to the co-operation of the senate in the appointment of officers, and the making of treaties; which are plainly qualifications of the general executive powers of appointing officers and making treaties.” “The difficulty of a complete enumeration of all the cases of executive authority, would naturally dictate the use of general terms, and would render it improbable that a specification of certain particulars was designed as a substitute for those terms, when antecedently used.

The different mode of expression employed in the constitution, in regard to the two powers, the legislative and the executive, serves to confirm this inference. In the article which gives the legislative powers of the government, the expressions are, ‘All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.’ In that which grants the executive power, the expressions are, ‘The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States.’

The enumeration ought therefore to be considered, as intended merely to specify the principal articles implied in the definition of executive power; leaving the rest to flow from the general grant of that power, interpreted in conformity with other parts of the Constitution, and with the principles of free government. The general doctrine of our Constitution then is, that the executive power of the nation is vested in the President; subject only to the exceptions and qualifications, which are expressed in the instrument.”"""Madison's response, which as I understand it, suggests that Hamilton's reading would bestow way more power on the Executive than intended:"""Madison’s reply to Hamilton, in five closely reasoned articles, was almost exclusively directed to Hamilton’s development of the contention from the quoted language that the conduct of foreign relations was in its nature an executive function and that the powers vested in Congress which bore on this function, such as the power to declare war, did not diminish the discretion of the President in the exercise of his powers. Madison’s principal reliance was on the vesting of the power to declare war in Congress, thus making it a legislative function rather than an executive one, combined with the argument that possession of the exclusive power carried with it the exclusive right to judgment about the obligations to go to war or to stay at peace, negating the power of the President to proclaim the nation’s neutrality. Implicit in the argument was the rejection of the view that the first section of Article II bestowed powers not vested in subsequent sections. “Were it once established that the powers of war and treaty are in their nature executive; that so far as they are not by strict construction transferred to the legislature, they actually belong to the executive; that of course all powers not less executive in their nature than those powers, if not granted to the legislature, may be claimed by the executive; if granted, are to be taken strictly, with a residuary right in the executive; or . . . perhaps claimed as a concurrent right by the executive; and no citizen could any longer guess at the character of the government under which he lives; the most penetrating jurist would be unable to scan the extent of constructive prerogative.” The arguments are today pursued with as great fervor, as great learning, and with two hundred years experience, but the constitutional part of the contentiousness still settles upon the reading of the vesting clauses of Articles I, II, and III."""

The Myers Case.—However much the two arguments are still subject to dispute, Chief Justice Taft, himself a former President, appears in Myers v. United States 22 to have carried a majority of the Court with him in establishing the Hamiltonian conception as official doctrine. That case confirmed one reading of the “Decision of 1789” in holding the removal power to be constitutionally vested in the President.23 But its importance here lies in its interpretation of the first section of Article II. That language was read, with extensive quotation from Hamilton and from Madison on the removal power, as vesting all executive power in the President, the subsequent language** was read as merely particularizing some of this power, and consequently the powers vested in Congress were read as exceptions which must be strictly construed in favor of powers retained by the President. Myers remains the fountainhead of the latitudinarian constructionists of presidential power

**By "subsequent language" it means the Sections in Article 2 that follow Section 1 enumerating some powers to be the province of the Executive Branch.

The above excerpts are from HERE. I edited the excerpts in a variety of ways...

.jpg)