Consumer good manufacturing is a highly competitive industry. There is constant pressure to reduce costs. Most of the costs producers face are Variable Costs. Variable Costs are costs that vary with production--they tend to increase as more is produced and decrease as less is produced. Bottom line: Variable Costs, well, vary with production (ceterus paribus).

Here is an analysis that centers of energy use in the production process. They suggest that it is an overlooked cost, even though it represents a significant portion of unit costs of producing a good. With careful analysis and remediation firms in manufacturing could save lots of cost by reducing the use of energy, hence lowering their Variable Costs.

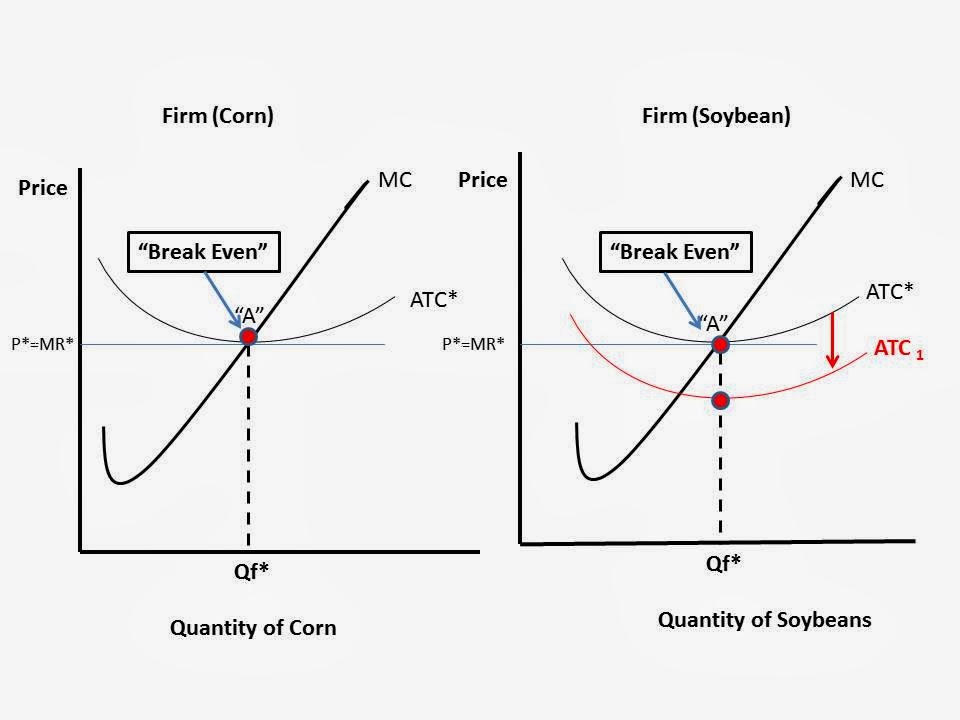

Read the selection (or go read the whole analysis--it is worth the time). The highlights are mine. Below it I inserted the graph of the firm that operates in a perfectly competitive market and illustrated how the firms cost curves are affected and in turn how production and profitability change.

A nice primer for an AP Microeconomics FRQ!

Bringing lean thinking to energy

Beset by rising costs, resource-intensive manufacturers are applying lean-management thinking in new ways to reduce the amount of energy used in production, to increase resource productivity—or both.

Over the years, many global manufacturers have secured big gains in labor and capital productivity by applying the principles of lean manufacturing. Fewer companies, however, have applied lean know-how to energy productivity. Line workers and even senior managers often consider energy a given when they consider it at all. The waste of energy and resources is typically overlooked or excluded from lean problem solving on the grounds that it is too complex for the front line to address, cuts across too many functions, or both.

That’s a mistake, given the importance of energy and raw materials as cost drivers. Indeed, for one LCD-television manufacturer we studied, energy represented 45 percent of total production costs. Meanwhile, for many “upstream” manufacturers (such as steel and chemical makers) energy typically accounts for up to 15 percent or more of overall production costs—the largest share after raw materials, which often account for at least 50 percent of the cost base. Our experience suggests that many of these manufacturers could reduce the amount of energy they use in production by as much as 30 percent (with similarly reduced resource losses), in part by applying lean principles and by shifting mind-sets to focus the organization on eliminating anything that doesn’t add value for customers.